Related Field: Pipe Organ Voicing

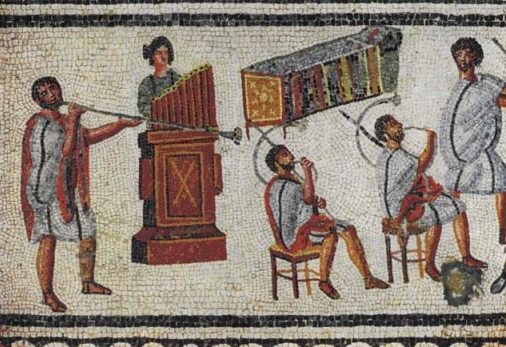

Perhaps the oldest work in aerodynamics—the study of moving air—can be found in an unexpected place. Long before wind tunnels and airfoils, before the Wright brothers and powered flight, airships and streamlined automobiles, pipe organ voicers figured out how to manipulate airflow to create a wide variety of sounds. Detail of the Zliten mosaic (2nd century CE), depicting the playing of several instruments including a hydraulis, the predecessor of the modern pipe organ. (image credit: Wikimedia Commons) A Brief History The roots of modern organs trace back to ancient Greece, where an engineer named Ctesibius invented a water-powered organ around 246 BCE called the hydraulis . This instrument disappeared from western Europe after the fall of Rome but evolved into the pipe organ in the Eastern Empire and was reintroduced around 800 CE. Since then, organs have underpinned Western music; the instrument shares its name, organum ("instrument" or "tool"), with the first ...